1. Executive summary

Cast aluminum combines low density, good specific strength, excellent castability and corrosion resistance with wide process flexibility.

Its properties are strongly dependent on alloy chemistry, casting method and post-cast treatments (e.g., heat treatment, surface finishing).

Understanding the physical constants, microstructural drivers, process–property relationships and common failure modes is essential for selecting cast aluminum for durable, lightweight, manufacturable components.

2. Introduction — why cast aluminum matters

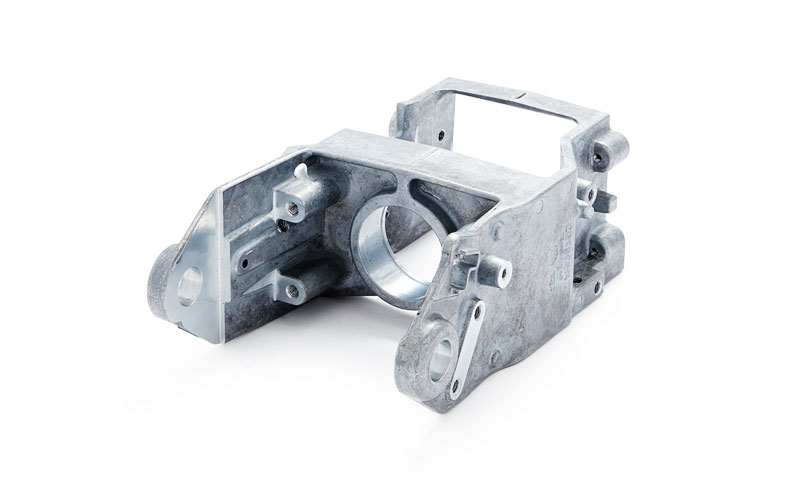

Aluminum castings are foundational in automotive, aerospace (non-critical parts), marine, consumer electronics, power transmission, heat exchangers, and general industrial equipment.

Designers choose cast aluminum when a complex geometry, integrated features, low part weight (specific strength/stiffness), and reasonable corrosion resistance are required.

The appeal is a combination of physical performance, manufacturing economy at scale, and recyclability.

3. Physical Properties of Cast Aluminum

| Property | Typical value | (notes) |

| Density (ρ) | 2.70 g·cm⁻³ (≈2700 kg·m⁻³) | Roughly one-third the density of steel |

| Melting point (pure Al) | 660.3 °C | Alloys melt over a range; Al–Si eutectic ≈ 577 °C |

| Young’s modulus (E) | ≈ 69 GPa | Modulus is relatively insensitive to alloying |

| Thermal conductivity | Pure Al ≈ 237 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹; cast alloys ≈ 100–180 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ | Alloying, porosity and microstructure reduce conductivity vs pure Al |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) | ~22–24 ×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹ | High relative to steels—important for multi-material assemblies |

Electrical conductivity (pure Al) |

≈ 37 ×10⁶ S·m⁻¹ | Cast alloys have lower conductivity; conductivity falls with alloying and porosity |

| Typical as-cast tensile strength | ~70–300 MPa | Wide range depending on alloy, casting method and porosity |

| Typical heat-treated (T6-type) tensile strength | ~200–350+ MPa | Applies to heat-treatable Al–Si–Mg casting alloys after solution-quench-age |

| Typical elongation (ductility) | ~1–12% | Varies strongly with alloy, microstructure and casting quality |

| Hardness (Brinell) | ≈ 30–120 HB | Highly dependent on alloy composition, Si content and heat treatment |

4. Metallurgy and microstructure of cast aluminum

Cast aluminum alloys are typically based on the aluminium (Al) matrix with controlled additions:

- Al–Si family (silumin) is the most widely used casting family because silicon improves fluidity, reduces shrinkage, and lowers melting range.

Microstructure: α-Al dendritic matrix with eutectic Si particles; morphology and distribution of Si strongly affect strength, ductility and wear. - Al–Si–Mg alloys are heat-treatable (age hardening via precipitates such as Mg₂Si).

- Al–Cu and Al–Zn cast alloys offer higher strength but can have reduced corrosion resistance and require careful heat treatment.

- Intermetallics (Fe-rich phases, Cu-Al phases) form during solidification and influence mechanical properties and machinability.

Controlled chemistry and treating (e.g., Mn for Fe modification) are used to limit deleterious intermetallic morphologies. - Dendritic segregation is inherent in solidification: primary α-Al dendrites and interdendritic eutectic; finer dendrite arm spacing (fast cooling) generally improves mechanical properties.

Important microstructural control mechanisms:

- Grain refinement (Ti, B additions or grain-refining inoculants) reduces hot tearing and improves mechanical properties.

- Modification (e.g., Sr, Na for Si modification) transforms plate-like Si into fibrous/rounded morphologies improving ductility and toughness.

- Degassing and hydrogen control are critical: dissolved hydrogen causes gas porosity; degassing and proper melt handling reduce porosity and improve fatigue.

5. Mechanical properties (strength, ductility, hardness, fatigue)

Strength and ductility

- Cast aluminum alloys span a wide strength/ductility spectrum.

As-cast tensile strengths for common Al–Si casting alloys typically fall in the lower-to-mid hundreds of MPa range when heat treated; unmodified, coarse eutectic microstructures and porosity lower strength and elongation. - Heat treatments (solution treatment, quench, artificial aging — commonly called T6) precipitate strengthening phases (e.g., Mg₂Si) and can significantly increase yield and ultimate tensile strengths.

Hardness

- Hardness correlates with alloying, primary Si content, and heat treatment. Hypereutectic Al–Si alloys (high Si) and heat-treated alloys show greater hardness and wear resistance.

Fatigue

- Cast aluminum generally has lower fatigue performance than wrought alloys of similar tensile strength because casting defects (porosity, oxide films, shrinkage) act as crack initiation sites.

Fatigue life is extremely sensitive to surface quality, porosity, and notch features. - Improving fatigue: reduce porosity (degassing, controlled solidification), refine microstructure, shot peen or surface finish, and use design to minimize stress concentrations.

Creep and elevated temperature

- Aluminium alloys have limited high-temperature strength vs steels; creep becomes relevant above ~150–200 °C for many casting alloys.

Selection for sustained elevated temperatures requires specialty alloys and design allowances.

6. Thermal and electrical properties

- Thermal conductivity: Cast aluminum retains good thermal conductivity compared to most structural metals, making it favorable for heat sinks, housings and components where heat transfer is important.

However, alloying, porosity and microstructure reduce conductivity compared with pure Al. - Thermal expansion: Relatively high CTE (~22–24×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) mandates careful tolerance and joint design with lower-CTE materials (steel, ceramics) to avoid thermal stress or seal failure.

- Electrical conductivity: Lower in cast alloys than pure Al; still used where weight-specific conductivity is important (e.g., busbars, housings combined with conductors).

7. Corrosion and environmental behaviour

- Native oxide protection: Aluminium spontaneously forms a thin, adherent Al₂O₃ oxide film that provides good general corrosion resistance in many atmospheres.

- Pitting in chloride environments: In aggressive chloride-containing environments (marine splash, deicing salts), localized pitting or crevice corrosion can occur, especially where intermetallics create micro-galvanic sites.

- Galvanic considerations: When coupled to more noble metals (e.g., stainless steel), aluminum is anodic and will corrode preferentially if electrically connected in an electrolyte.

- Protective measures: Alloy selection, coatings (anodizing, conversion coatings, paints, powder coat), sealants at joints and design to avoid crevices improve long-term corrosion performance.

8. Casting processes and how they affect properties

Different casting routes produce characteristic microstructures, surface finishes, tolerances and mechanical properties:

- Sand casting: Low tooling cost, good design flexibility, coarser microstructure, higher porosity risk, rough surface finish. Typical for large, low-volume parts. Mechanical properties generally lower than die casting.

- Die (high-pressure) casting: Thin-walled, close tolerances, excellent surface finish and high production rates.

Rapid solidification yields fine microstructure and good mechanical properties, but die castings often contain gas and shrinkage porosity; many die-cast alloys are not heat-treatable in the same way as sand-cast Al–Si–Mg alloys. - Permanent-mold casting (gravity): Improved microstructure vs sand casting (lower porosity, better mechanical properties), moderate tooling cost.

- Investment (lost-wax) casting: Excellent surface finish and complex geometries, used for precision parts at moderate volumes.

- Centrifugal casting / squeeze casting: Useful where high integrity and directional solidification are required (cylindrical parts, castings for pressure-containing applications).

Process–property trade-offs:

- Faster cooling (die casting, permanent mold with chills) → finer dendrite arm spacing → higher strength and ductility.

- Porosity control (degassing, pressurized casting) → critical for fatigue-sensitive applications.

- Economic choice depends on part size, complexity, unit cost and performance requirements.

9. Heat treatment, alloying, and microstructure control

This section summarizes how alloy chemistry, casting practice and post-cast thermal processing interact to determine the microstructure — and therefore the mechanical, fatigue and corrosion properties — of cast aluminum.

Key alloying elements and their effects

| Alloying element | Typical range in cast Al alloys | Primary metallurgical effects | Benefits | Potential drawbacks / considerations |

| Silicon (Si) | ~5–25 wt% (Al–Si alloys) | Forms Al–Si eutectic; controls fluidity and shrinkage; influences Si particle morphology | Excellent castability; reduced hot cracking; improved wear resistance | Coarse plate-like Si reduces ductility unless modified (Sr/Na) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | ~0.2–1.0 wt% | Forms Mg₂Si; enables precipitation hardening (T6/T5 tempers) | Significant strength increase; good weldability; improved age-hardening response | Over-addition increases porosity sensitivity; requires good quench control |

| Copper (Cu) | ~2–5 wt% | Strengthening via Al–Cu precipitates; increases high-temperature stability | High strength potential; good elevated-temperature performance | Reduced corrosion resistance; increased hot-tear risk; may affect fluidity |

| Iron (Fe) | Typically ≤0.6 wt% (impurity) | Forms Fe-rich intermetallics (β-AlFeSi, α-AlFeSi) | Necessary tolerance for recycled feedstock; improves melt handling | Brittle phases reduce ductility and fatigue life; Mn additions often required |

| Manganese (Mn) | ~0.2–0.6 wt% | Modifies Fe intermetallics into more benign morphologies | Improves ductility and toughness; increases tolerance to Fe impurities | Excess Mn can form sludge at low temperatures; affects fluidity |

Nickel (Ni) |

~0.5–3 wt% | Forms Ni-rich intermetallics with good thermal stability | Enhances high-temperature strength and wear resistance | Increases brittleness; reduces corrosion resistance; higher cost |

| Zinc (Zn) | ~0.5–6 wt% | Contributes to age-hardening in certain alloy systems | High strength in Al–Zn–Mg–Cu systems | Less common in castings; can reduce corrosion resistance |

| Titanium (Ti) + Boron (B) (grain refiners) | Added as master alloys | Promote fine, equiaxed grain structure | Reduces hot tearing; improves mechanical uniformity | Excess may reduce fluidity; must be carefully controlled |

| Strontium (Sr), Sodium (Na) (modifiers) | ppm-level additions | Modify eutectic Si from plate-like to fibrous/rounded | Dramatically improves elongation and toughness; better fatigue behaviour | Excess Na causes porosity; Sr requires tight control to avoid fading |

| Zirconium (Zr) / Scandium (Sc) (microalloying) | ~0.05–0.3 wt% (varies) | Form stable dispersoids that prevent grain growth during heat treatment | Excellent high-temperature stability; improved strength | High cost; used mainly in aerospace or specialty alloys |

Precipitation (age) hardening — mechanisms and stages

Many cast Al–Si–Mg alloys are heat-treatable through precipitation hardening (T-temp families). The general sequence:

- Solution treatment — hold at elevated temperature to dissolve soluble phases (e.g., Mg₂Si) into a homogeneous supersaturated solid solution.

Typical solution temperatures for common Al–Si casting alloys are high enough to approach but not exceed incipient melting; times depend on section thickness. - Quench — rapid cooling (water quench, polymer quench) to retain a supersaturated solid solution at room temperature.

The quench rate must be sufficient to avoid premature precipitation that reduces hardening potential. - Aging — controlled reheating (artificial aging) to precipitate fine strengthening particles (e.g., Mg₂Si) that impede dislocation motion.

There is often a peak-hardness condition (peak age); further aging causes coarsening and overaging (reduced strength, increased ductility).

Stages of precipitation typically proceed from Guinier-Preston (GP) zones (coherent, very fine) → semi-coherent fine precipitates → incoherent coarser precipitates.

The coherent/semicoherent precipitates produce the strongest strengthening effect.

Two common temper designations:

- T6 — solution-treated, quenched and artificially aged to a peak strength (common for A356/T6 and similar alloys).

- T4 — natural (room-temperature) aging after quench (no artificial aging step) — gives different property balance and is used in particular applications.

Practical consequence: heat-treatable cast alloys (Al–Si–Mg family) can have their tensile strength and yield strength increased substantially with T6 processing, often at the cost of some ductility and increased sensitivity to casting defects (quench demands, distortion).

Advanced approaches and specialty treatments

- Retrogression and re-aging (RRA): used in some wrought alloys to recover properties after thermal excursions; less common for castings but applicable in niche cases.

- Two-step aging or multi-stage aging: can optimise strength–ductility balance; specific recipes tuned for alloy and section.

- Microalloying with Zr/Sc/Be: in performance alloys Zr or Sc form dispersoids that pin grain growth during heat treatment and improve high-temperature stability; cost consideration is high.

- Hot isostatic pressing (HIP): reduces internal porosity and can improve fatigue life for high-integrity castings (investment casting, high-value aerospace parts).

10. Surface finishing and joining considerations

- Anodizing: electrochemical thickening of the oxide for wear, corrosion resistance and cosmetic finish. Good for castings if designed for uniform current distribution.

- Conversion coatings (chromate or non-chrome alternatives): improve paint adhesion and corrosion resistance; chromates historically used but increasingly replaced for environmental reasons.

- Painting / powder coating: common for aesthetics and added corrosion protection; surface prep (cleaning, etching) is critical.

- Machining: cast aluminum generally machines well, especially Al–Si alloys with free-machining grades developed for die-casting. Intermetallics and hard Si particles affect tool wear.

- Welding: many cast alloys can be welded, but care must be taken: heat-affected zones can create cracking or porosity; repair welding often requires preheat, appropriate filler metals and post-weld treatments.

Some high-Si cast alloys are difficult to weld and are better repaired mechanically.

11. Sustainability, economics, and lifecycle considerations

- Recyclability: aluminum is highly recyclable; recycled (secondary) aluminum dramatically reduces energy use vs primary production (commonly cited energy savings up to ~90% compared with primary aluminium).

- Lifecycle costs: lower part weight often reduces operating energy in transportation applications; initial casting costs must be balanced with maintenance, coatings and end-of-life recycling.

- Material circularity: casting scraps and end-of-life parts are readily remelted; careful alloy control is needed to avoid buildup of impurities (Fe being a common problem).

12. Comparative Analysis: Cast Aluminum vs. Competitors

| Property / Material | Cast Aluminum | Cast Iron (Gray & Ductile) | Cast Steel | Magnesium Casting Alloys | Zinc Casting Alloys |

| Density | ~2.65–2.75 g/cm³ | ~6.8–7.3 g/cm³ | ~7.7–7.9 g/cm³ | ~1.75–1.85 g/cm³ | ~6.6–7.1 g/cm³ |

| Typical Cast Strength | 150–350 MPa (T6: 250–350 MPa) | Gray: 150–300 MPa; Ductile: 350–600 MPa | 400–800+ MPa | 150–300 MPa | 250–350 MPa |

| Thermal Conductivity | 100–180 W/m·K | 35–55 W/m·K | 40–60 W/m·K | 70–100 W/m·K | 90–120 W/m·K |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good (oxide film) | Moderate; rusts without coatings | Moderate to poor | Moderate; coatings often needed | Good |

| Castability / Manufacturability | Excellent fluidity; great for complex shapes | Good for sand casting; lower fluidity | Higher melting point, more difficult to cast | Very good; ideal for high-pressure die casting | Excellent for die casting; high precision |

Relative Cost |

Medium | Low | Medium–High | Medium–High | Low–Medium |

| Key Advantages | Lightweight; corrosion resistant; excellent castability | High strength & damping; low cost | Very high strength & toughness | Lightest structural metal; rapid casting cycles | Excellent dimensional accuracy; thin-wall capability |

| Key Limitations | Lower stiffness; porosity risk | Heavy; poor corrosion without coatings | Heavy; heat treatment needed | Lower corrosion resistance; flammability in melt | Heavy; low melting point limits high-temp use |

13. Conclusions

Cast aluminum is a versatile, high-value engineering material whose performance is determined as much by alloy chemistry and post-process treatments as by the metal itself.

When properly specified, produced and maintained, cast aluminum delivers a compelling combination of low density, good specific strength, high thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance and excellent castability—advantages that make it the material of choice for automotive housings, heat-exchange components, control enclosures and many consumer and industrial applications.

FAQs

Is cast aluminum weaker than wrought aluminum?

Not inherently; many cast alloys can achieve competitive strengths, particularly after heat treatment.

However, castings are more susceptible to casting-specific defects (porosity, inclusions) that reduce fatigue performance compared with wrought, wrought-and-formed alloys.

Which casting process gives the best mechanical properties?

Processes that promote rapid, controlled solidification and low porosity (permanent mold, die casting with proper degassing, squeeze casting) typically yield better mechanical properties than coarse sand castings.

Can cast aluminum be heat-treated?

Yes—many Al–Si–Mg casting alloys are heat-treatable (T6-type) to substantially increase strength via solution treatment, quench, and aging.

How do I prevent porosity in castings?

Reduce dissolved hydrogen (degassing), control melt turbulence, use proper gating and risering, apply filtration, and optimize pouring temperature and mold design.

Is cast aluminum good for marine environments?

Aluminum offers good general corrosion resistance due to passive oxide formation but is vulnerable to localized chloride-induced pitting and galvanic corrosion; appropriate alloy choice (marine-grade alloys), coatings and design are required for long-term marine service.