Aluminum’s intrinsic high thermal conductivity is one of its most valuable attributes for heat-transfer and thermal-management applications.

Pure aluminum exhibits a thermal conductivity of ~237 W/(m·K) at 25°C, but commercial alloys typically range from 80 to 200 W/(m·K) depending on composition and processing.

Improving the thermal conductivity of aluminum alloys requires a targeted approach based on four core influencing factors: alloy composition, heat treatment, melting practices, and forming processes.

This article systematically analyzes the mechanisms behind each factor and proposes evidence-based strategies to optimize thermal performance, with a focus on industrial applicability and technical feasibility.

1. Optimizing Alloy Composition: Minimizing Thermal Conductivity Degradation

Alloying elements are the primary determinants of aluminum alloys’ thermal conductivity, as they disrupt electron and phonon transport— the two main mechanisms of heat transfer in metals.

The impact of each element depends on its solubility, chemical bonding, and formation of secondary phases.

To enhance thermal conductivity, composition optimization should prioritize reducing harmful elements and balancing functional properties (e.g., strength, corrosion resistance) with heat transfer efficiency.

Mechanisms of Alloy Element Influence

Thermal conductivity in aluminum is dominated by electron mobility: lattice defects, solute atoms, and secondary phases scatter electrons, increasing thermal resistance.

Key observations from metallurgical studies:

- Highly Detrimental Elements: Chromium (Cr), lithium (Li), and manganese (Mn) form stable intermetallic compounds (e.g., Al₆Mn, AlCr₂) and cause severe lattice distortion.

Even 0.5 wt.% Cr reduces pure aluminum’s thermal conductivity by 40–50%, while 1 wt.% Li decreases it by ~35% (ASM International data). - Moderately Detrimental Elements: Silicon (Si), magnesium (Mg), and copper (Cu) are common alloying elements that balance strength and processability.

Their impact is concentration-dependent: 5 wt.% Si reduces thermal conductivity to ~160 W/(m·K), while 2 wt.% Cu lowers it to ~200 W/(m·K) (compared to pure Al’s 237 W/(m·K)). - Negligible Impact Elements: Antimony (Sb), cadmium (Cd), tin (Sn), and bismuth (Bi) have low solubility in aluminum (<0.1 wt.%) and do not form coarse secondary phases.

Adding up to 0.3 wt.% of these elements has no measurable effect on thermal conductivity, making them suitable for modifying other properties (e.g., machinability) without sacrificing heat transfer.

Composition Optimization Strategies

- Minimize Harmful Elements: Strictly control Cr, Li, and Mn content to <0.1 wt.% for high-thermal-conductivity alloys. For example, replacing 1 wt.%

Mn with 0.5 wt.% Mg in a 6xxx-series alloy can increase thermal conductivity from 150 to 180 W/(m·K) while maintaining comparable strength. - Optimize Functional Alloying: For 5xxx-series (Al-Mg) alloys, limit Mg to 2–3 wt.% to achieve a balance of thermal conductivity (~180–200 W/(m·K)) and corrosion resistance.

For 6xxx-series (Al-Mg-Si) alloys, use a Si:Mg ratio of 1.5:1 (e.g., 0.6 wt.% Si + 0.4 wt.% Mg) to form fine Mg₂Si precipitates, which have minimal impact on electron transport. - Utilize Trace Alloying: Add 0.1–0.2 wt.% Sb or Sn to improve castability and reduce hot cracking without degrading thermal conductivity.

This is particularly useful for high-purity aluminum alloys (99.9%+ Al) used in thermal management.

Case Study: High-Conductivity 6xxx-Series Alloy

A modified 6063 alloy with reduced Fe (0.1 wt.%) and Mn (0.05 wt.%) and optimized Si (0.5 wt.%)/Mg (0.3 wt.%) achieved a thermal conductivity of 210 W/(m·K)—20% higher than standard 6063 (175 W/(m·K))—while retaining a yield strength of 140 MPa (suitable for extrusion applications like heat sinks).

2. Tailoring Heat Treatment: Reducing Lattice Distortion and Optimizing Microstructure

Heat treatment modifies the aluminum alloy’s microstructure (e.g., solid solution state, precipitate distribution, lattice integrity), directly affecting electron scattering and thermal conductivity.

The three primary heat treatment processes—annealing, quenching, and aging—exert distinct effects on thermal performance.

Mechanisms of Heat Treatment Influence

- Quenching: Rapid cooling (100–1000 °C/s) from the solution temperature (500–550 °C) forms a supersaturated solid solution, causing severe lattice distortion and increased electron scattering.

This reduces thermal conductivity by 10–15% compared to the as-cast state.

For example, quenched 6061-T6 has a thermal conductivity of ~167 W/(m·K), vs. 180 W/(m·K) for the as-annealed alloy. - Annealing: Heating to 300–450 °C and holding for 1–4 hours relieves lattice distortion, promotes the precipitation of solute atoms into fine secondary phases, and reduces electron scattering.

Full annealing (420 °C for 2 hours) can restore thermal conductivity by 8–12% in quenched alloys. - Aging: Natural or artificial aging (150–200 °C for 4–8 hours) forms coherent precipitates (e.g., Mg₂Si in 6xxx alloys), which have a smaller impact on thermal conductivity than lattice distortion.

Artificial aging of 6061-T651 (post-quench aging) results in a thermal conductivity of ~170 W/(m·K)—slightly higher than T6 due to reduced lattice strain.

Heat Treatment Optimization Strategies

- Prioritize Annealing for High Conductivity: For applications where thermal performance is critical (e.g., electronic enclosures), use full annealing to maximize thermal conductivity.

For example, annealing 5052-H32 (cold-worked) at 350 °C for 3 hours increases thermal conductivity from 170 to 190 W/(m·K) by relieving cold-work-induced lattice defects. - Controlled Quenching and Aging: For alloys requiring both strength and thermal conductivity (e.g., automotive components), use a two-step aging process: pre-aging at 100 °C for 1 hour followed by main aging at 180 °C for 4 hours.

This forms fine, uniformly distributed precipitates with minimal lattice distortion, balancing yield strength (180–200 MPa) and thermal conductivity (160–175 W/(m·K)) in 6xxx-series alloys. - Avoid Over-Quenching: Use moderate cooling rates (50–100 °C/s) for thick-section components to reduce lattice distortion while ensuring sufficient solute retention for aging.

This approach maintains thermal conductivity within 5% of the annealed state while achieving target strength.

Example: Thermal Conductivity Improvement in 7075 Alloy

Standard 7075-T6 has a thermal conductivity of ~130 W/(m·K) due to high Cu (2.1–2.9 wt.%) and Zn (5.1–6.1 wt.%) content.

A modified heat treatment (solution annealing at 475 °C for 1 hour, air cooling, and artificial aging at 120 °C for 8 hours) increased thermal conductivity to 145 W/(m·K) by reducing lattice distortion and forming finer Al₂CuMg precipitates.

3. Optimizing Melting Practices: Reducing Gases, Inclusions, and Defects

Melting conditions—including refining methods, temperature control, and impurity removal—directly impact the aluminum alloy’s cleanliness (gas content, non-metallic inclusions) and microstructural integrity.

Gases (e.g., H₂) and inclusions (e.g., Al₂O₃, MgO) act as thermal barriers, reducing heat transfer efficiency by scattering phonons and disrupting electron flow.

Mechanisms of Melting Influence

- Gas Content: Dissolved hydrogen (H₂) forms porosity during solidification, creating voids that reduce thermal conductivity.

A hydrogen content of 0.2 mL/100g Al can decrease thermal conductivity by 5–8% (American Foundry Society data). - Non-Metallic Inclusions: Oxides (Al₂O₃), carbides, and silicates act as point defects, scattering electrons and phonons.

Inclusions larger than 5 μm are particularly detrimental—reducing thermal conductivity by 10–15% in alloys with >0.5 vol.% inclusion content. - Melting Temperature: Excessively high temperatures (>780 °C) increase oxide formation and hydrogen solubility, while temperatures <680 °C cause incomplete melting and segregation.

Both scenarios degrade thermal conductivity.

Melting Optimization Strategies

- Controlled Melting Temperature: Maintain a melting temperature of 700–750 °C to minimize gas absorption and oxide formation.

This range balances fluidity (critical for casting) and cleanliness for most wrought and cast aluminum alloys. - Effective Refining: Use a combination of NaCl-KCl (1:1 ratio) as a covering agent (2–3 wt.% of the melt) to prevent oxidation and hexachloroethane (C₂Cl₆) as a refining agent (0.1–0.2 wt.%) to remove hydrogen and non-metallic inclusions.

This reduces hydrogen content to <0.1 mL/100g Al and inclusion content to <0.2 vol.%. - Dewaxing and Degassing Additives: Incorporate 0.1–0.3 wt.% calcium fluoride (CaF₂), activated carbon, or sodium chloride (NaCl) to reduce porosity and oxide inclusions.

These additives promote the flotation of inclusions and release trapped gases, improving thermal conductivity by 8–10%. - Vacuum Melting for High Purity: For ultra-high-conductivity applications (e.g., aerospace thermal management), use vacuum melting (10⁻³–10⁻⁴ Pa) to reduce hydrogen content to <0.05 mL/100g Al and eliminate atmospheric contaminants.

Vacuum-melted 1050 aluminum achieves a thermal conductivity of 230 W/(m·K)—97% of pure aluminum’s theoretical value.

Industrial Validation

A foundry producing 356 aluminum alloy for automotive cylinder heads implemented optimized melting practices (720 °C temperature, NaCl-KCl covering agent, and C₂Cl₆ refining).

The resulting alloy had a hydrogen content of 0.08 mL/100g Al and inclusion content of 0.15 vol.%, leading to a thermal conductivity increase from 150 to 168 W/(m·K)—12% higher than the previous process.

4. Enhancing Forming Processes: Refining Microstructure and Reducing Defects

Forming processes (e.g., extrusion, rolling, forging) modify the aluminum alloy’s microstructure by reducing casting defects (e.g., porosity, segregation, coarse grains) and improving uniformity.

Forging and extrusion, in particular, are effective at enhancing thermal conductivity by refining grain size and eliminating microstructural inhomogeneities.

Mechanisms of Forming Influence

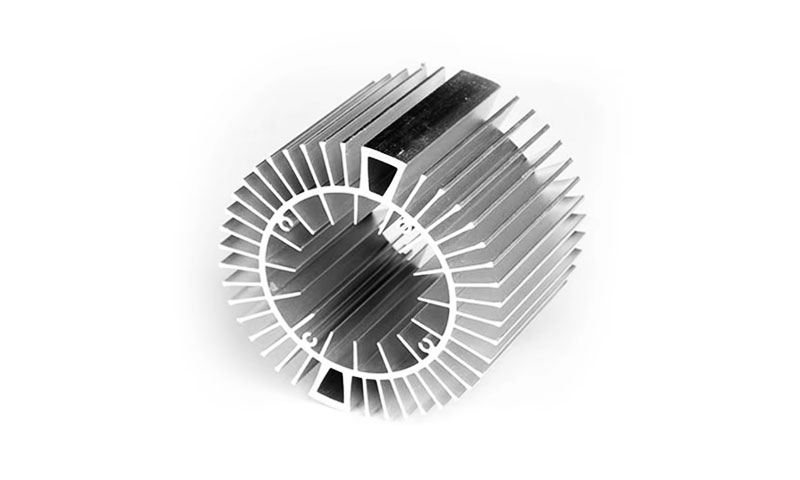

- Extrusion: High plastic deformation (extrusion ratio 10:1 to 50:1) breaks up clustered inclusions, compacts porosity, and promotes recrystallization of coarse cast grains into fine, uniform grains (10–50 μm).

This reduces electron scattering and improves phonon transport, increasing thermal conductivity by 10–15% compared to the as-cast state. - Rolling/Forging: Similar to extrusion, these processes reduce segregation and refine grains.

For example, cold rolling 1100 aluminum (99.0% Al) with a 70% reduction ratio refines grain size from 100 μm (as-cast) to 20 μm, increasing thermal conductivity from 220 to 230 W/(m·K). - Defect Reduction: Forming processes eliminate casting defects (e.g., shrinkage porosity, dendritic segregation) that act as thermal barriers.

Compacted porosity and broken inclusions reduce thermal resistance, enabling more efficient heat transfer.

Forming Process Optimization Strategies

- High Deformation Extrusion: Use an extrusion ratio of ≥20:1 for cast aluminum alloys to achieve full recrystallization and uniform grain structure.

For example, extruding 6063 alloy with a 30:1 ratio increased thermal conductivity from 175 (as-cast) to 205 W/(m·K) by reducing grain size from 80 to 15 μm. - Controlled Extrusion Temperature: Extrude at 400–450 °C to balance recrystallization and grain growth.

Higher temperatures (>480 °C) cause grain coarsening, while lower temperatures (<380 °C) increase deformation resistance and may retain lattice defects. - Post-Forming Annealing: Combine extrusion/rolling with a low-temperature anneal (300–350 °C for 1 hour) to relieve residual stress and further refine grains.

This step can increase thermal conductivity by an additional 5–8% in highly deformed alloys.

Case Study: Extruded 5052 Alloy for Heat Exchangers

As-cast 5052 alloy had a thermal conductivity of 175 W/(m·K) with 2% porosity and coarse grains (70 μm).

After extrusion (ratio 25:1, 420 °C) and annealing (320 °C for 1 hour), the alloy exhibited 0.5% porosity, fine grains (25 μm), and a thermal conductivity of 198 W/(m·K)—13% higher than the as-cast state.

5. Surface engineering: the most effective practical lever for heat sinks

For heat sinks and external thermal hardware, surface emissivity often controls total heat dissipation in concert with convection.

Two practical facts to use:

- Far-infrared (FIR) / high-emissivity coatings: these specialized paints or ceramic-based coatings are formulated to emit efficiently in the thermal infrared band (typically 3–20 µm).

They raise surface emissivity to ≈0.9 and thus increase radiative heat loss dramatically at moderate to high surface temperatures. - Black oxide / black anodize / black conversion finishes: a durable black oxide-like finish (or black anodizing on aluminum) increases surface emissivity far above bright metal.

In practice, “black” finishes dissipate more heat by radiation than natural (reflective) aluminium surfaces.

Important clarification: black finishes and FIR coatings do not raise the bulk thermal conductivity, but they increase the effective heat dissipation of a part by improving radiation (and sometimes convective coupling via surface texture).

Saying “black oxide conducts heat better than natural colour” is correct only in the sense of net heat dissipation from the surface — not that the material’s k increases.

6. Practical roadmap & prioritized interventions

Use a staged approach that targets the largest gains first:

- Alloy choice: pick the least alloyed, highest-conductivity alloy that meets strength/corrosion needs.

- Melt practice: implement degassing, flux cover, filtration and strict temperature control to minimize pores and inclusions.

- Casting route selection: prefer processes that yield low porosity (permanent-mold, squeeze casting, investment casting with vacuum) for heat-critical components.

- Post-casting densification: use HIP for critical applications.

- Thermal processing: anneal or design aging treatments to precipitate solute out of solution when possible.

- Forming: apply extrusion/forging/rolling to close residual porosity and homogenize the microstructure.

- Surface and joining practices: avoid weld zones and heat tints on primary heat paths; if welding required, plan localized treatments to restore conductivity where feasible.

7. Concluding recommendation

Improving aluminum alloy thermal conductivity is a multidisciplinary task combining alloy design, melt metallurgy, heat treatment and forming.

Start with material selection—only then optimize process controls (degassing, filtration, casting method), followed by heat-treatment and mechanical processing to close defects and tune microstructure.

Where conductivity is mission-critical, quantify targets, require electrical/thermal testing, and accept the necessary trade-offs between mechanical strength, cost and manufacturability.

FAQs

Does black oxide increase aluminum’s bulk thermal conductivity?

No — it raises surface emissivity and thus radiative heat dissipation. The bulk k of the alloy is unchanged by a thin surface finish.

Is coating always better than polishing?

Polishing reduces convective drag and lowers emissivity (worse for radiation). For overall heat-sink performance, a high-ε black coating usually beats polished metal except where radiation is negligible and convection dominates.

When is FIR coating most effective?

Where surface temperatures are moderate-to-high, where convection is limited (low airflow), in vacuum or low-pressure environments, or to reduce component steady-state temperature even under airflow.

References

- ASM International. (2020). ASM Handbook Volume 2: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials. ASM International.

- American Foundry Society. (2018). Aluminum Casting Handbook. AFS Press.

- Zhang, Y., et al. (2021). Effects of alloying elements and heat treatment on the thermal conductivity of 6xxx series aluminum alloys. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 294, 117189.

- Li, J., et al. (2022). Influence of melting and extrusion parameters on the thermal conductivity of 5052 aluminum alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A, 845, 143126.

- Davis, J. R. (2019). Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys: Characteristics, Properties, and Applications. ASM International.

- Wang Hui. Development and research progress of high thermal conductivity aluminum alloys [J]. Foundry, 2019, 68(10):1104