1. Executive summary

“Cast aluminum–magnesium” refers to two related but distinct engineering families:

(A) high-Mg cast Al–Mg alloys (Mg-majority alloying to maximize corrosion resistance and specific strength for marine/weight-critical parts) and (B) Al–Si–Mg casting alloys (Al–Si base with modest Mg additions used for age hardening and strength).

Al–Mg cast alloys deliver excellent corrosion resistance (especially in chloride environments), attractive strength-to-weight and good toughness, but they pose casting and melt-handling challenges because Mg oxidizes readily and can promote porosity if process discipline is weak.

Most Al–Mg cast alloys are not strongly precipitation-hardening — strengthening occurs primarily by solid solution, microstructure control and thermomechanical processing rather than conventional T6 routes used for Al–Si-Mg alloys.

2. What we mean by “cast Al–Mg” — families and common grades

Two practical categories of cast Al–Mg alloys appear repeatedly in industry:

- Category A — High-Mg cast alloys (Al–Mg family): alloys in which Mg content is high enough to dominate corrosion behavior and specific density/strength.

In literature and shop practice this class commonly cites Mg in the 3–6 wt% range with small Si additions (≈0.5–1.0 %) when better castability is needed. These are used where corrosion resistance / light weight is primary. - Category B — Al–Si–Mg casting alloys (Al–Si–Mg family): near-eutectic Al–Si base cast alloys (Si ≈ 7–12 wt%) that include modest Mg (≈0.2–0.8 wt%) to permit artificial aging (Mg₂Si precipitation) and higher strength after T-type ageing (T6).

Examples include industry workhorse alloys such as A356 (Al–Si–Mg) — these are sometimes called “Al–Mg containing castings” (but are primarily Al–Si alloys with Mg as a strengthening element).

In practice you will select Category A when corrosion resistance (marine, chemical contact) and low density are dominant; choose Category B when castability, dimensional stability and heat-treatable strength are required.

3. Typical chemical compositions

Table: Typical composition ranges (engineering guidance)

| Family / Example | Al (balance) | Mg (wt%) | Si (wt%) | Cu (wt%) | Others / notes |

| High-Mg cast Al–Mg (typical) | balance | 3.0 – 6.0 | 0.0 – 1.0 | ≤ 0.5 | Small Mn, Fe; Si added (~0.5–1.0%) to improve fluidity when needed. |

| Al–Si–Mg (e.g., A356 / A357 style) | balance | 0.2 – 0.6 | 7.0 – 12.0 | 0.1 – 0.5 | Mg present to enable Mg₂Si precipitation hardening (T6). |

| Low-Mg Al casting (for comparison) | balance | < 0.2 | variable | variable | Typical die-casting alloys (A380 etc.) — Mg minor. |

Notes

- The ranges above are practical engineering windows — exact specifications must reference a standards designation (ASTM/EN) or the supplier’s certificate.

- High-Mg cast alloys approach the composition region of wrought 5xxx alloys but are engineered for casting (different impurity control and solidification behavior).

4. Microstructure and phase chemistry — what controls performance

Primary microstructural players

- α-Al matrix (face-centred cubic): the primary load-bearing phase in all Al alloys.

- Mg in solid solution: Mg atoms dissolve in α-Al; at moderate concentrations they strengthen the matrix by solid-solution strengthening.

- Intermetallics / second phases:

-

- Mg-rich intermetallics (Al₃Mg₂/β): can form at high Mg levels and at interdendritic regions; their morphology and distribution control high-temperature stability and corrosion behavior.

- Mg₂Si (in Al–Si–Mg alloys): forms during aging and is the principal precipitation hardening phase in the Al-Si-Mg family.

- Fe-bearing phases: Fe impurities form brittle intermetallics (Al₅FeSi, etc.) that reduce ductility and can promote localized corrosion; Mn is often added in small amounts to modify Fe phases.

Solidification characteristics

- High-Mg alloys tend to have a relatively simple α + intermetallic solidification path but may show segregation if cooling is sluggish; fast cooling refines structure but raises the risk of porosity if feeding is inadequate.

- Al–Si–Mg alloys solidify with primary α followed by a eutectic α + Si; Mg participates in later reactions (Mg₂Si) if Mg content suffices.

Microstructure → properties link

- Fine, uniformly distributed second phases give better toughness and avoid brittle behavior.

- Coarse intermetallics or segregation degrade fatigue, ductility and corrosion performance. Control via melt practice, grain refiners and cooling rate is crucial.

5. Key performance characteristics

Mechanical properties (typical engineering ranges — cast state)

Values vary by alloy, section size, casting process and heat treatment. Use supplier data for design-critical numbers.

- Density (typical): ~2.66–2.73 g·cm⁻³ for Al–Mg cast alloys (slight increase versus pure Al ~2.70).

- Tensile strength (as-cast):

-

- High-Mg cast alloys: ~150–260 MPa (depending on Mg content, section thickness and finish).

- Al–Si–Mg (cast + T6): ~240–320 MPa (T6 aged A356 ranges at the top end).

- Yield strength: roughly 0.5–0.8 × UTS as a guide.

- Elongation:5–15% depending on alloy and processing — high-Mg castings typically exhibit good ductility (single-phase tendency), Al–Si with coarse Si will show lower elongation unless modified.

- Fatigue and fracture toughness: good when microstructure is sound and porosity low; fatigue performance sensitive to casting defects.

Corrosion resistance

- High-Mg cast alloys show excellent general corrosion resistance, especially in marine and alkaline environments — Mg raises pitting resistance compared with standard 3xxx/6xxx Al alloys.

- For chloride-rich environments, Al–Mg alloys often outperform plain Al alloys but are still inferior to stainless steels and require surface protection in severe cases.

Thermal properties

- Thermal conductivity of Al–Mg alloys remains high (≈ 120–180 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ depending on alloying and microstructure), making them suitable for thermal housings and heat-dissipating parts.

Manufacturability & welding

- Casting methods: sand casting, permanent mold, gravity die-casting and some high-pressure die casting (with careful fluxing) are used.

- Weldability: Al–Mg alloys are generally weldable (GTAW, GMAW), but welding of cast sections requires attention to porosity and post-weld corrosion (use appropriate filler alloys and post-weld cleaning).

- Machinability: fair; tool selection and speeds adjusted for aluminum alloys.

6. Heat-treatment and thermal processing

Which alloys respond to heat treatment?

- Al–Si–Mg cast alloys (Category B) are heat-treatable (age-hardening): solution treat → quench → artificial aging (T6) produces significant strength increases via precipitation of Mg₂Si.

Typical T6 schedules for A356/A357: solution ~495 °C, age at 160–180 °C for several hours (follow supplier guidance). - High-Mg cast Al–Mg alloys (Category A) are generally not precipitation-hardenable to the same degree: Mg is a solid-solution strengthener and many high-Mg compositions harden primarily by strain aging or cold work in wrought forms rather than conventional T6 ageing.

Heat treatment for cast high-Mg alloys focuses on:

-

- Homogenisation to reduce chemical segregation (low-temperature soak to redistribute solute).

- Stress-relief anneal to remove casting stresses (typical temperatures: modest anneals 300–400 °C — exact cycles depend on alloy and section).

- Careful solution treatment: used selectively for some cast Al–Mg variants, but may promote undesirable intermetallic coarsening — consult alloy datasheets.

Practical heat-treatment guidance

- For Al–Si–Mg castings intended for strength, plan for solution + quench + aging (T6) and design with section sizes that quench effectively.

- For high-Mg castings, specify homogenisation and stress-relief cycles to stabilize microstructure and dimensional stability; do not expect large age-hardening gains.

7. Foundry practice and processing considerations

Melting and melt protection

- Magnesium control: Mg oxidises easily to MgO. Use protective cover fluxes (salt flux), controlled superheat, and minimize dross formation.

- Melt temperature: keep within recommended ranges for the chosen alloy; excessive superheat increases burn losses and oxide formation.

- Degassing and filtration: remove hydrogen and oxides (rotary degassing, ceramic foam filters) to reduce porosity and improve mechanical/corrosion performance.

Casting methods

- Sand casting & permanent-mold: common for high-Mg alloys and for larger parts.

- Gravity die casting / low-pressure casting: produces better microstructure and surface finish; good for structural parts.

- High-pressure die casting: used mainly for Al–Si based alloys; caution with high-Mg content due to Mg oxidation and gas porosity.

Common defects & mitigation

- Porosity (gas/shrinkage): mitigated by degassing, filtration, proper gating and riser design, and by controlling solidification rate.

- Oxide/bifilm defects: control pouring turbulence and use filtration.

- Hot tearing: manage via design (avoid abrupt section changes) and control feeding/solidification.

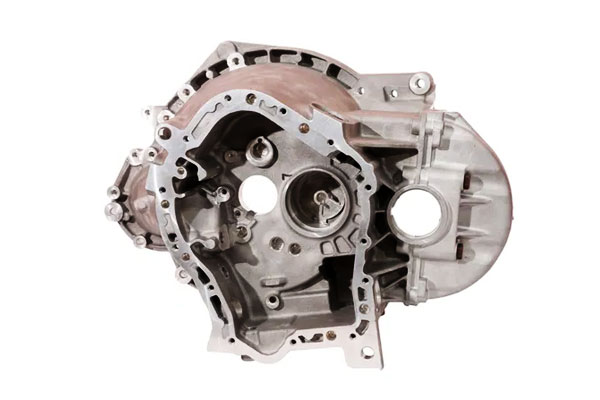

8. Typical Applications of Cast Aluminum–Magnesium Alloys

Cast aluminum–magnesium alloys occupy an important middle ground in light-metal engineering: they combine lower density and improved corrosion resistance relative to many aluminium alloys with acceptable castability and good toughness.

Marine and offshore equipment

- Pump housings, valve bodies and impellers for fresh/brackish water service

- Deck fittings, service brackets, gussets and shrouds in splash/spray zones

- Pipe fittings, condenser housings and service enclosures

Automotive and transportation

- Structural brackets and subframes (low-mass sections)

- Body in white components, interior structural housings and enclosures

- Heat-sink housings and carrier plates for power electronics (in EVs)

Pumps, valves and fluid-handling hardware (industrial)

- Pump casings and volutes for chemical and water handling

- Valve bodies, seat housings and actuator housings

Heat dissipation and electronics housings

- Electronic housings, thermal spreaders and motor controller enclosures (EV traction/inverters)

- Heat-sink housings where thermal conductivity and low mass are important

Aerospace (non-primary structures and secondary components)

- Interior brackets, housings, avionics enclosures, non-primary structural panels and fairings

Consumer & sporting goods, electronics

- Lightweight frames, protective casings, portable device housings, bicycle components (non-critical), camera bodies

Industrial machinery and HVAC components

- Fan housings, blower casings, heat exchanger end-caps, lightweight pump covers

Specialty applications

- Cryogenic equipment (where low mass is advantageous but alloys must be qualified for low-temperature toughness)

- Offshore instrumentation housings, subsea shallow components (with adequate protection)

9. Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of Cast Aluminum–Magnesium Alloys

- Superior corrosion resistance (especially in marine environments)

- Low density and high specific strength for weight-critical applications

- Excellent gas tightness for pressure vessels and sealed systems

- Good machinability for precision finishing

Disadvantages of Cast Aluminum–Magnesium Alloys

- Poor casting performance with high hot-tear tendency and low fluidity

- Oxidation risk and slag inclusion requiring protective atmospheres

- Higher production costs due to process complexity and material premiums

- Limited application scope restricted to high-value sectors

10. Comparative Analysis: Cast Al–Mg vs. Competing Alloys

The table below compares cast aluminum–magnesium alloys (Cast Al–Mg) with commonly competing casting materials used in lightweight and corrosion-sensitive applications.

The comparison focuses on key engineering decision criteria rather than only nominal material properties, enabling practical material selection.

| Attribute / Criterion | Cast Al–Mg Alloy | Cast Al–Si Alloy | Cast Magnesium Alloy | Cast Stainless Steel |

| Density | Low (≈1.74–1.83 g·cm⁻³) | Moderate (≈2.65–2.75 g·cm⁻³) | Very low (≈1.75–1.85 g·cm⁻³) | High (≈7.7–8.0 g·cm⁻³) |

| Corrosion resistance | Very good (especially marine/splash) | Good to moderate (depends on Si and Cu) | Moderate (requires protection) | Excellent (chloride-resistant grades) |

| Tensile strength (as-cast / treated) | Medium | Medium to high (with heat treatment) | Low to medium | High |

| Toughness / impact resistance | Good | Fair to good (brittle Si phases possible) | Fair | Excellent |

| High-temperature capability | Limited (≤150–200 °C typical) | Moderate (Al–Si–Cu better) | Poor | Excellent |

| Castability | Good | Excellent (best overall) | Good | Moderate |

| Porosity sensitivity | Medium (requires melt control) | Medium | High | Low to medium |

| Machinability | Good | Excellent | Excellent | Fair |

| Thermal conductivity | High | High | High | Low |

| Galvanic compatibility | Moderate (needs isolation) | Moderate | Poor | Excellent |

| Surface finishing options | Good (anodize, coatings) | Excellent | Limited | Excellent |

| Cost (relative) | Medium | Low to medium | Medium | High |

| Typical applications | Marine fittings, pump housings, lightweight structures | Automotive castings, housings, engine parts | Electronics housings, ultra-light components | Valves, pressure parts, corrosive environments |

Material Selection Summary

Choose cast aluminum–magnesium alloys when lightweight, corrosion resistance, and reasonable strength are required at moderate temperatures.

For extreme environments (high temperature, pressure, or aggressive chemicals), stainless steel remains superior, while Al–Si alloys dominate when complex casting geometry and cost efficiency are paramount.

11. Conclusions — practical engineering takeaways

- Cast Al–Mg alloys provide an excellent combination of low density, corrosion resistance and adequate strength for many structural applications — but they are not a single material; distinguish high-Mg cast families from Al–Si–Mg heat-treatable casting families.

- Process discipline matters: melt protection, degassing and filtration are essential to achieve expected mechanical and corrosion performance.

- Heat-treatability differs: Al–Si-Mg cast alloys respond well to solution + aging (T6) and deliver higher strengths; high-Mg cast alloys gain less from conventional ageing and depend more on microstructure control and mechanical processing.

- Design for casting: control section thickness, feeding and gating to avoid common casting defects that most adversely affect fatigue and corrosion performance.