1. ʻO ka hōʻuluʻuluʻana

Case hardening creates a thin, very hard surface layer (the “case”) on a tougher, ʻokiʻia nā core. It combines surface wear and fatigue resistance with a ductile core that resists shock.

Typical uses are gears, Nā papahele, Nā Nele, pins and bearings. Achieving excellent functional performance is an engineering task (metralurgy, Ke kaʻina hanaʻana, distortion management, nānā).

Making the part look great requires planning: control where and how finishes are produced, sequence polishing/grinding relative to heat treatment, and finish with an appropriate protective and decorative surface treatment (E.g., controlled temper colors, 'OLleloʻEleʻele, Pvd, holoholo).

2. What is case hardening?

Kālā Hardna (Ua kāheaʻia surface hardening) is the family of metallurgical processes that produce a hard, wear-resistant surface layer — the case — on a part while leaving a relatively soft, ductile interior — the kuai.

The objective is to combine high surface hardness and wear/fatigue resistance me core toughness and impact resistance, delivering components that resist surface damage without becoming brittle through-and-through.

Core concepts

- Paakiki (case): a thin zone (typically tenths of a millimetre to a few millimetres) engineered to be hard (E.g., 55–64 HRC for carburized martensite or 700–1,200 HV for nitrides).

- Ductile core: the bulk material remains relatively soft and tough to absorb shocks and avoid catastrophic brittle fracture.

- Gradual transition: a controlled hardness gradient from the surface into the core (not an abrupt interface) to improve load transfer and fatigue life.

- Localized treatment: case hardening can be applied to entire parts or selectively to functional zones (bearing journals, gear teeth, contact faces).

3. Common case-hardening processes

Below I describe the principal case-hardening technologies you will encounter in engineering practice.

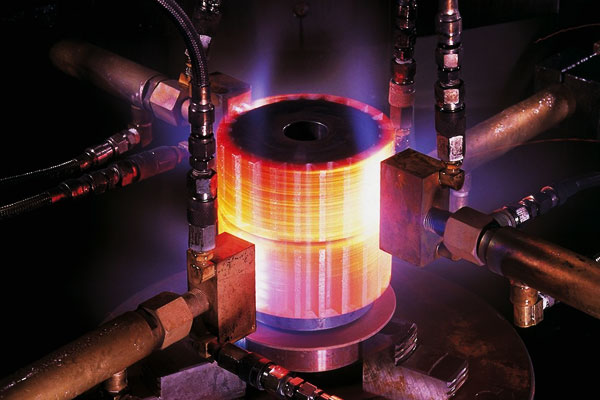

Carpurize (aila, vacuum and pack variants)

Mea lihua: carbon is diffused into the steel surface at elevated temperature to raise the near-surface carbon content; the part is then quenched to form a martensitic case and tempered to achieve the required combination of hardness and toughness.

Nā Kūlana & Kūlike:

- Aila carpurize (industrial standard): performed in a controlled hydrocarbon atmosphere (endothermic gas or natural gas mixtures) at roughly 880-950 ° C.

Carbon potential and soak time determine case depth; practical effective case depths commonly range from 0.3 mm i 2.5 mm for many components; surface hardness after quench/temper typically 58-62 hrc for high-carbon martensite. - Haka (haʻahaʻa haʻahaʻa) carpurize: uses hydrocarbon injection in a vacuum furnace, often at 900-1050 ° C with subsequent high-pressure gas quench.

Advantages include minimal oxidation/scale, excellent carbon control and lower residual distortion; this route is favored where surface appearance and tight tolerances are required. - Pack (luhi) carpurize: older shop method using carbonaceous powders at 900-950 ° C; lower capital cost but poorer control and cleanliness—less suited for appearance-critical parts.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: can produce relatively deep, tough martensitic cases; well understood and economical for medium–large production.

Cons: quenching from high temperature causes significant thermal stress and potential distortion; surface oxidation and scaling must be managed (especially in conventional gas or pack carburizing).

Kākoʻo Kāleleka

Mea lihua: a combined diffusion of carbon and nitrogen into the surface at temperatures generally lower than carburizing, followed by quench and temper.

Nitrogen increases surface hardness and may improve wear and scuff resistance relative to carburized only cases.

Kūlike: typical process temperatures are 780-880 ° C; effective case depths are shallower than carburizing, maʻamau 0.1-1.0 mm, and surface hardnesses after quench/temper land around 55–60 HRC for appropriate steels.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: faster cycles and good as-machined wear properties; produces a tougher, nitrogen-enriched case beneficial for abrasive or adhesive wear.

Cons: shallower case depth limits use under high contact stresses; Ke kaʻina hanaʻana (atmosphere purity, ammonia level) is critical to avoid undesirable compound layers or color irregularities.

Nitriding (aila, plasma/ion, and salt bath)

Mea lihua: nitrogen diffuses into steel at relatively low temperatures to form hard nitrides (E.g., FeN, Crn, AlN) within a diffusion zone; no quench is required because the process generally occurs below the austenitizing temperature.

The result is a hard, wear-resistant surface with very low distortion.

Nā Kūlana & Kūlike:

- Aila nitriding: performed at 480–570 °C in an ammonia-based atmosphere; case depths typically 0.05–0.6 mm (diffusion zone), with surface hardness often in the 700–1,200 HV range depending on steel chemistry and time.

- Plasma (ion) nitriding: uses a low-pressure glow discharge to activate nitrogen; offers superior uniformity, better control of the compound (keʻokeʻo) Palapika, and a clean surface finish—advantages for aesthetic parts.

Typical temperatures are 450-550 ° C with adjustable bias to tune surface finish. - Salt-bath nitriding / nitrocarburizing (E.g., Tenifer, Melonite): chemically active baths at ~560–590 °C produce good wear and corrosion characteristics but require careful environmental and waste handling.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: minortion minuma, excellent fatigue and wear performance, improved corrosion resistance in many cases, and attractive, consistent finishes (especially plasma nitriding).

Cons: diffusion layer is relatively thin compared with carburizing; steels must contain nitride-forming elements (AL, Cr, V, No) for best results; harmful compound layers (“white layer”) can form if parameters are not controlled.

ʻO ka paʻakikī paʻakikī

Mea lihua: high-frequency electromagnetic induction rapidly heats a surface layer to austenitizing temperature; a rapid quench (water or polymer) transforms the heated layer to martensite.

Because heating is local and very fast, hardening can be applied selectively and cycle times are short.

Nā hiʻohiʻona maʻamau: surface temperatures often in the range 800-1100 ° C for short times (kekona), with case depths controlled by frequency and time—from 0.2 mm up to several millimetres. Surface hardness commonly 50–65 HRC depending on steel and quench.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: highly localized hardening (Kāhele, gear flanks, journals), very high throughput, reduced cycle energy, and reduced overall distortion relative to full-part quench if properly fixtured.

Cons: requires geometry amenable to induction coils; edge overheating or flash can produce discoloration; limitations on minimum wall thickness and effective hardenability of the chosen steel.

Flame hardening

Mea lihua: surface heating by oxy-fuel flame to austenitizing temperature followed by quench.

A relatively simple field-repair capable technique that mimics induction hardening but uses flame as the heat source.

Typical conditions: surface heating to ~800-1000 ° C immediately followed by quenching; case depths often 0.5–4 mm depending on heat input and quench.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: flexible for large or field repairs, low capital equipment needs.

Cons: less uniform heat application than induction; higher risk of scale, oxidation and visual discoloration; greater skill required to achieve consistent aesthetic results.

Ferritic nitrocarburizing and low-temperature thermochemical processes

Mea lihua: low-temperature surface enrichment of nitrogen and carbon while the steel is in the ferritic state (below A1), producing a hard compound layer and diffusion zone without transforming the bulk microstructure.

Typical systems: salt bath ferritic nitrocarburizing or gas variants at ~560–590 °C produce shallow hard layers with improved wear and corrosion resistance and low distortion.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: maikaʻi loa, improved corrosion resistance and a characteristic dark matte finish that is useful for appearance.

Cons: environmental concerns with certain salt baths (choose environmentally compliant processes) and limited case depth.

Thin hard coatings (Pvd, Cvd, Dlc) — not diffusion cases but often used with case hardening

Mea lihua: physical or chemical vapor deposition deposits a very thin, extremely hard layer (Kū, Crn, Ō'ō, Dlc) onto a substrate.

These are not diffusion cases; they rely on adhesion and thin-film mechanics rather than a graded metallurgical transition.

Typical attributes: coating thickness typically a few micrometres; hardness in the thousands of HV; visually striking (gold TiN, black DLC) and excellent wear/tribological performance.

ʻO ka pōmaikaʻi: excellent decorative finishes and additional wear resistance; compatible with nitrided substrates for improved adhesion and fatigue behavior.

Cons: coatings are thin—do not replace the need for a diffusion case where contact fatigue or deep wear resistance is required—adhesion depends on surface prep and substrate condition.

4. Material suitability and selection

| Kaʻohana waiwai | Typical steels / Nā hiʻohiʻona | Preferred processes | Aesthetic tendencies |

| Nā kāhiko haʻahaʻa haʻahaʻa | 1018, 20Mncr5, 8620 | Carpurize, carbonitriding | Gas carburizing → uniform color; solid pack → variable |

| Nā kiki | 4140, 4340, 52100 | Induction, nitriding (if nitride elements present) | Plasma nitriding → golden/brown or matte finishes |

| Nā mea kanu lāʻau | 316, 420 | Plasma nitriding (careful), Pvd | Nitrided stainless → subtle color, ʻO ke kū'ēʻana o ka corrossion maikaʻi |

| Hae hao | Hinahina, ʻO Dāhihi | Nitriding (select grades), laha halima | Porous structure → less uniform color; needs finishing |

| Nā mea hana hāmeʻa / Hss | AISI H11, D2 | Nitriding, Pvd, huhū | PVD/DLC deliver premium colors (gula, ʻeleʻele) |

5. Key Strategies to Optimize the Appearance of Case-Hardened Surfaces

Achieving a “great look” requires a systematic approach that integrates pre-treatment preparation, process parameter control, post-treatment finishing, and defect prevention.

Each step directly impacts surface aesthetics and functional performance.

Pre-lāʻau lapaʻau: The Foundation of Aesthetic Uniformity

Nā mea haumia (pono, ailakalu, 'ōwili, kūkaku) and material defects (Potiwale, Nāʻalā) are amplified during case hardening, leading to uneven color, 'ōwaha, or coating failure.

Pre-treatment steps must ensure a clean, uniform surface:

- Degreasing and Cleaning: Use ultrasonic cleaning (with alkaline detergents) or vapor degreasing (with trichloroethylene) to remove oil and grease.

Avoid chemical cleaners that leave residues (E.g., chloride-based solutions), which cause pitting during heat treatment.

According to ASTM A380, the surface must have a water-break-free finish (no beading) after cleaning. - Ke kālaiʻana a me ka polish: For aesthetic-critical parts, Ke hōʻoia nei (surface roughness Ra ≤ 0.8 }m) a he polish (Ra ≤ 0.2 }m) remove scratches, Nā māka, a me nā meaʻonaʻole.

This ensures uniform heat absorption and diffusion during case hardening, preventing localized discoloration. - Shot Blasting/Pickling: Pana pua (with glass beads or aluminum oxide) removes rust and scale, improving surface adhesion for post-treatment.

Pickling (with dilute hydrochloric acid) is used for heavy scaling but must be followed by neutralization to avoid surface etching.

Post-Treatment Finishing: Enhancing Aesthetics and Functionality

Post-treatment transforms the as-hardened surface into a visually appealing finish while preserving or enhancing functional properties (ʻaʻa, Ke kū'ē neiʻo Corrosionion).

The choice of finishing method depends on the base process, waiwai, a me nā koi kūpono:

Mechanical Finishing

- ʻO ka hoʻopololei: For carburized or induction-hardened parts, sequential polishing (coarse to fine abrasives: 120 grit → 400 grit → 800 git) achieves a mirror finish (Ra ≤ 0.05 }m).

Use diamond abrasives for hard surfaces (HRC ≥ 60) to avoid scratching. Polishing after nitriding enhances the golden-brown color and improves corrosion resistance. - Kauhele: Use a cotton or felt wheel with polishing compounds ('Ainuiʻo ALXIE PAUL, Chromium Oxide) to create a glossy finish.

Buffing is ideal for decorative parts (E.g., trim trim, jewelry fasteners) but may reduce surface hardness slightly (by 2–5 HRC). - ʻO ka panaʻana: For non-glossy, matte finishes, shot peening with fine glass beads (0.1-0.3 mm) creates a uniform texture while improving fatigue strength. The surface roughness can be controlled between Ra 0.4–1.6 μm.

Chemical and Electrochemical Finishing

- ʻO ka Cover Oxide Cover: Also known as bluing, this process forms a thin (0.5-1.5 μm) black iron oxide (Lihuaipuai) film on the surface. It is compatible with carburized and nitrided parts, providing a uniform black finish with mild corrosion resistance.

The process (ASTM D1654) uses a hot alkaline solution (135–145℃) and requires post-oiling to enhance aesthetics and corrosion protection. - Electroplating: ʻO Chrome ka paʻa (ʻO BRROMY HARD, decorative chrome) or nickel plating can be applied after case hardening to create a glossy, ʻO ka hoʻopauʻana o Corrosionion-resistant.

Ensure the surface is free of scale and porosity (via pre-polishing) to avoid plating defects (bubbling, peeling). Decorative chrome plating achieves a mirror finish with a Vickers hardness of 800–1000 HV. - Ke kūlohelohe meleʻana: PhoPshanging (zinc phosphate, manganese phosphate) forms a gray or black crystalline film that improves paint adhesion.

It is used for parts requiring both aesthetics and corrosion resistance (E.g., nā'āpana loea).

Anodizing is suitable for stainless steel nitrided parts, producing a range of colors (polū, ʻeleʻele, gula) via electrolytic oxidation.

Coating Technologies for Advanced Aesthetics

- ʻO ka waihoʻana i ke kino kino (Pvd): Pvd coatings (Kū, Ō'ō, Crn) are applied via vacuum deposition, producing thin (2-5 μM), hāwana, and visually consistent films.

TiN offers a golden finish (popular in cutting tools and luxury hardware), while CrN provides a silver-gray finish. PVD is compatible with nitrided parts and enhances both aesthetics and wear resistance.'Olunuiʻo Aluminim'oxe pvd back - Ke kūʻai aku nei i ka mea kūʻai (Cvd): CVD coatings (ʻO ka carbon-like carbom, Dlc) create a matte black or glossy finish with exceptional hardness (HV ≥ 2000) a me ke kū'ēʻana.

They are ideal for high-performance parts (E.g., Na'Āpanaʻo Aerospace) but require high-temperature processing (700–1000℃), which may affect the core properties of case-hardened parts.

6. Nā hemahema maʻamau, root causes, and prevention

| Hewa ole | Typical root cause | Kinohi |

| 'Ōwaha / Oxiyan | Oxygen in furnace / poor atmosphere control | Vacuum processes, inert purge, strict PO₂ control |

| Discoloration / blotchiness | Uneven heating, inconsistent atmosphere | Uniform heating, atmosphere monitoring, plasma nitriding for uniformity |

| White layer (brittle nitride) | Excessive ammonia / high nitriding energy | Control NH₃, bias, wa; remove thin white layer if needed |

| Pitting | Chloride contamination / residual salts | Residue-free cleaning, neutralization after pickling |

| Warpage / Kauhai | Uneven quench / asymmetric geometry | Balanced design, polymer/quench control, Nā Mea Mola, vacuum HP quench |

| Adhesion failure of coatings | Surface porosity or oil residues | ʻO ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe kūpono, surface preps, Ke kāohi neiʻo Poosity, adhesion tests |

7. Aesthetic design considerations for case-hardened components

A visually successful case-hardened part is the product of integrated design, process selection and finishing — not an afterthought.

Specify process consistency for color matching

If parts are intended to be seen together (gear sets, fastener kits, assemblies), require the same hardening and post-treatment route across the set.

Plasma nitriding followed by a given post-finish ('OLleloʻEleʻele, clear lacquer or PVD) produces highly repeatable tones;

mixing fundamentally different processes (for example carburizing on one part and nitriding on another) makes consistent color and surface response difficult to achieve and should be avoided when visual uniformity is required.

Use deliberate texture contrast to create visual hierarchy

Combine matte and polished zones to emphasize form and function.

ʻo kahi laʻana, a polished nitrided tooth flank contrasted with a shot-peened or bead-blasted hub creates an attractive, engineered look while serving functional needs (polished teeth reduce friction; matte hubs improve grip and hide handling marks).

Define texture targets quantitatively (Ra or surface finish class) so finishers can reproduce the effect.

Design geometry to control thermal effects and dimensional stability

Geometry influences heating, cooling and distortion during surface hardening. Add generous fillets, avoid sharp abrupt section changes, and balance cross-sectional mass to reduce the risk of edge overheating and warpage.

For induction hardening, observe practical minimum section rules (typical minimum wall/thickness ≈ 3 mm) and allow for fixturing to ensure uniform heating.

Where tight post-hardening tolerances are required, plan for rough machining before treatment and finish grinding afterward.

Integrate corrosion-protection into the aesthetic plan

No ka waho, marine or exposed architectural use, combine the case hardening route with durable corrosion finishes that preserve color over time.

Nā hiʻohiʻona: plasma-nitrided stainless steel followed by a clear DLC or PVD topcoat for long-term color stability; carburized housings that receive electroless nickel or powder coating on non-sliding areas.

Specify compatible coating systems and curing/pretreatment steps (Kanui, hoʻoili, PALATEPATE) to avoid adhesion problems and maintain appearance.

Protect functional surfaces and plan masking/assembly

Decide early which surfaces must retain the diffusion case (bearing journals, nā helehelena hōʻailona) and which may receive decorative coatings.

Use masking or removable inserts during finishing when coatings would impair function.

Where mating surfaces must remain uncoated, document this in drawings and process sheets to avoid accidental coverage.

Tolerancing and finish sequence control

Document the finish sequence: rough machine → harden → finish grind/polish → final coating. State dimensional tolerances after hardening if no post-grind is planned.

For aesthetic quality, e wehewehe i ka ʻae ʻana (color reference, gloss or matte target, allowable blemishes) and require photographic or sample approvals on first articles.

8. Application-Specific Aesthetic Optimization Examples

The following examples illustrate how to tailor case hardening and finishing for different industries, balancing aesthetics and functionality:

Nā'āpana automotive (Kauluhi, Nā papahele, Trim)

For transmission gears (20MnCr5 steel): Gas carburizing (case depth 1.0 mm) → quenching + tempering → precision grinding (Ra 0.4 }m) → black oxide coating. This achieves a uniform black finish with high wear resistance.

For luxury aitompetitive Trim (4140 Kukui Kekuhi): Plasma nitriding (golden-brown finish) → buffing → clear PVD coating. The clear coating preserves the golden color and enhances corrosion resistance.

Precision Tools (ʻOkiʻana i nā hana hana, Wrenches)

For cutting tools (HSS steel): Nitriding (case depth 0.2 mm) → TiN PVD coating. The golden TiN finish is visually distinctive and provides exceptional wear resistance.

For wrenches (1045 Kukui Kekuhi): Induction hardening → shot peening (ʻO ka hoʻopauʻana Matte) → manganese phosphating. The gray phosphate finish improves grip and prevents rust.

Architectural Hardware (Door Handles, Railings)

For stainless steel door handles (316 Kukui Kekuhi): Plasma nitriding → anodizing (black or bronze) → clear coat. The anodized finish offers color customization and weather resistance.

For cast iron railings: Flame hardening → sandblasting (matte texture) → powder coating. Powder coating provides a durable, uniform finish in a range of colors.

9. Sustaintability, safety and cost considerations

- Ikaika & EUMSISIONS: heat treating is energy-intensive. Vacuum carburizing reduces emissions from combustion but uses electricity and gas pulses. Optimize cycle times and load density to reduce footprint.

- Kaʻona & palekana: avoid legacy cyanide or hexavalent chromium salts. Prefer vacuum, aila, plasma or environmentally controlled salt baths with approved waste handling.

- Nā Kūlana Kūʻai: ke koho koho (vacuum vs gas vs induction), manawa manawa, secondary grinding and finishing, scrapping rates due to distortion.

Choose process matched to required performance: vacuum carburize for precision, nitriding for low distortion, induction for low volume localized hardening. - Ke Kekauple & hōʻano hou: nitrided and PVD finishes extend life with low rework; induction hardening enables field re-hardening in some cases.

10. Hopena

Case hardening is a versatile surface modification technology that, when optimized, can deliver both superior functional performance and exceptional aesthetics.

The key to a “great look” lies in systematic process control (pre-lāʻau lapaʻau, parameter optimization, post-finishing) and application-specific tailoring (koho koho, defect prevention, design integration).

Chemical processes like plasma nitriding offer inherent aesthetic advantages (uniform color, minimal deformation), while thermal processes like induction hardening require more post-treatment to achieve visual appeal.

Advanced finishing technologies (Pvd, DLC coatings) bridge the gap between functionality and aesthetics, enabling case-hardened parts to meet the demands of high-end applications.

FaqS

What is the difference between case depth and case hardness?

Case depth is the thickness of the hardened/diffused layer; case hardness is the hardness at or near the surface.

Both must be specified because a thin very-hard case may fail rapidly, while a deep but soft case may not resist wear.

Should I polish before or after case hardening?

Critical functional surfaces (bearing journals, nā helehelena hōʻailona) should be finish-ground NA MEA hāwanaʻu. Pre-hardening polishing is acceptable only for decorative surfaces that won’t be ground later.

How deep should the case be for gears?

Typical gear faces are carburized to 0.6-1.5 mm effective case depth (depth to a defined hardness) depending on load. Heavy-duty gears may require deeper cases or through-hardening alternatives.

Is nitriding “better” than carburizing?

It depends. Nitriding gives very low distortion, excellent surface hardness, and better corrosion resistance in some environments, but the case is thinner and nitrided surfaces lack the martensitic core toughness obtainable by carburizing + Quetch. Choose by application.

How to avoid cracking after case hardening?

Control material chemistry, use proper preheat and quench practice, use appropriate temper cycles and reduce retained austenite (subzero if necessary).

Avoid hard, brittle untempered microstructures on thin sections.

Can PVD be applied over a carburized surface?

Yes — but surface preparation (ʻO ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe, possibly thin diffusion barrier) and control of deposition parameters are required for adhesion.

PVD layers are thin and primarily decorative/wear-enhancing, not a substitute for a diffusion case.